Nightmares are a common theme in those diagnosed with PTSD. When asked about how he would explain PTSD in his own words, Abe replied:

"People ask me, 'When were you in Vietnam?'

When was I in Vietnam? I was there last night. I was there this morning. Five minutes ago before you asked me. And I will probably go back tonight."

Staff Sergeant Tom Frame fishes as one way to escape his PTSD. The peaceful hobby allows him to focus on one thing and keeps his mind from wandering.

Gary Young was a medic. It took many years and his daughters' demands for him to finally see a VA psychiatrist. The psychiatrist had to use hypnosis to get Gary to open up, not because he refused but because he suppressed his memories.

In a collaborative photograph, Josh Quigg creates an image that describes what it means to live with PTSD. He wants to be there for his family, but sometimes the PTSD pulls him back to Afghanistan. (Photo by Kara Frame and Joshua Quigg)

Gary Young holds his youngest grandson, Ethan. His wife, Betty, explains that it’s his grand-babies that bring the most joy to Gary and helps him avoid his PTSD.

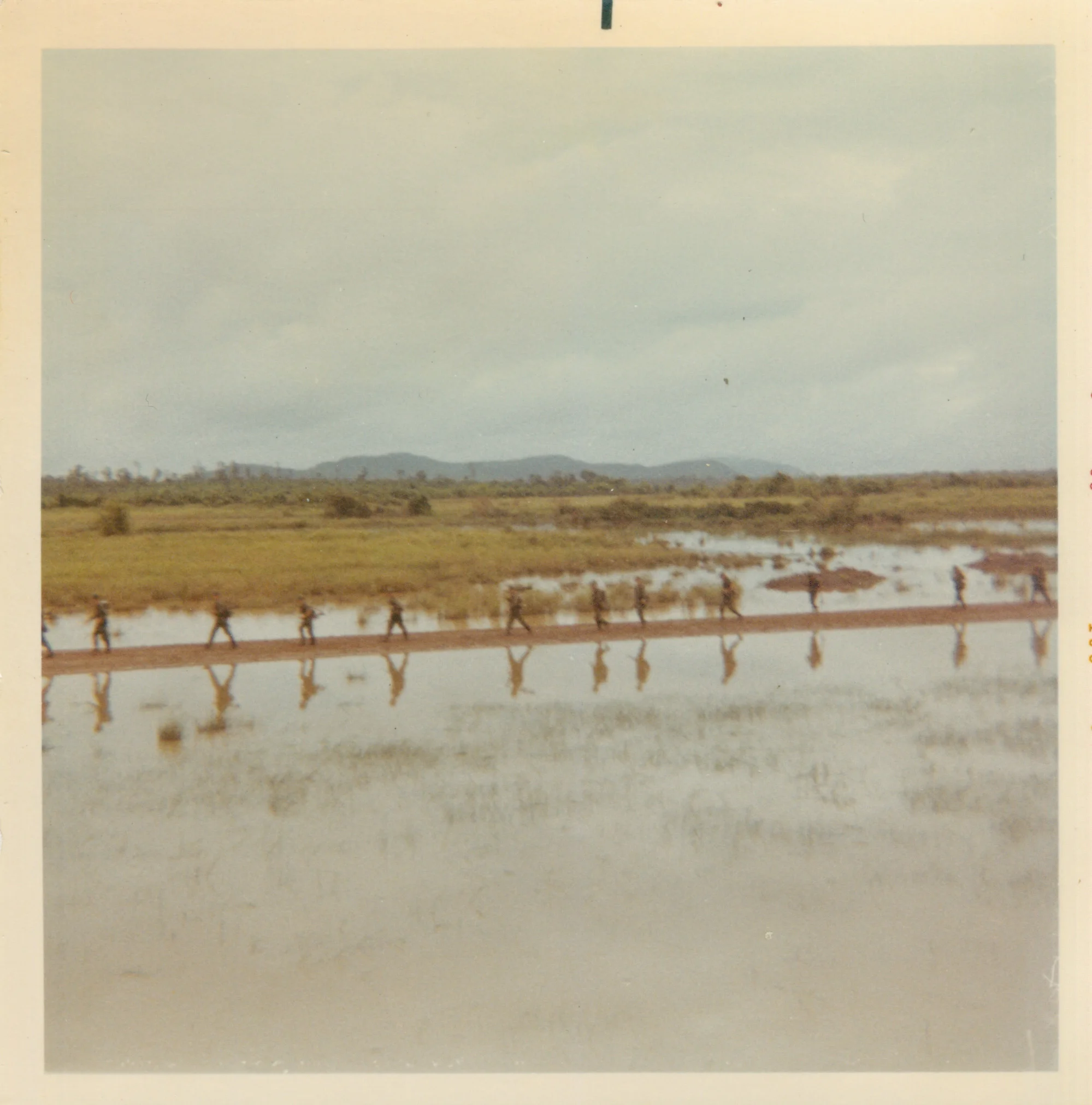

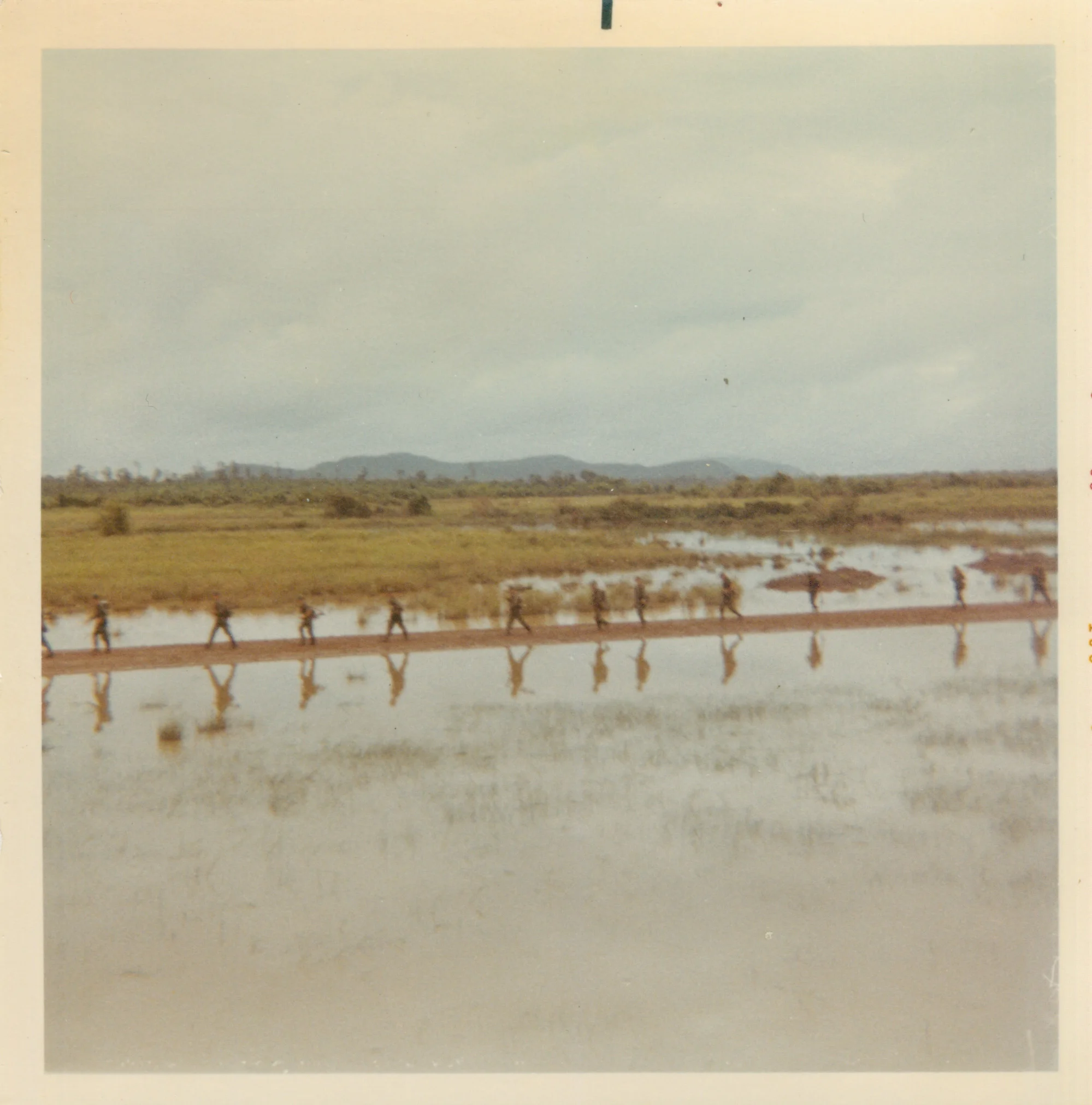

The 1st Battalion (Mechanized), 5th Infantry walk North out of Dau Tieng, Vietnam in the summer of 1968. On August 21st, the unit was ambushed and they lost 17 men in the Battle of Ben Cui. (Photograph by Donald Elverd)

Abe Cardenas rests his head in his hands as he waits for his nutrient-rich formula to drip down his feeding tube, which can take hours. In addition to PTSD, Abe suffered from throat and prostate cancer - both of which the VA acknowledges as presumptive diseases from exposure to Agent Orange. As a result of the throat cancer, he received a tracheotomy.

Frame at Fort Bragg, North Carolina in 1967. Over 40 years later he is still haunted by the date of August 21st, 1968 when a few thousand North Vietnamese ambushed his unit of 90 men. He lost 17 of his “brothers.” He talks about going to the National Vietnam War Memorial for the first time in 1984. He says it was the first time he saw all of his brothers together again.

Quigg was medically retired from the US Army after being deemed unfit to serve due to his PTSD diagnosis. Plans of a life career were shattered as the young Quigg family uprooted from Texas and moved back home to Arizona. It took a year and a half for them to find a home of their own.

Frame receives a hug from a friend on Memorial Day. He has marched in his local Memorial Day parade for over thirty years with his family there in support.

Betty Young would try to stay away from Gary when he was angry or she could tell he was having a “bad day.” So she often stayed busy. Having put one grandson to sleep, she spends time on her iPad before leaving to go pick the other one up from daycare.

The Quigg family notices a significant difference between who Josh was before he left for Afghanistan and who he is now after returning home. They say what they miss most is his carefree jokester attitude and his smile.

Abe and ChaCha Cardenas were engaged to be married when his draft notice arrived. Abe wrote to ChaCha constantly as she awaited his return. But when he came home, PTSD, anger, and alcoholism came with him.

Gary and Betty met after his return from Vietnam. They dated for two months before getting married. Betty always told her mother she would marry a man who politely kissed her on her hand – which Gary did on their first date.

When asked about how his life is affected by PTSD, Josh Quigg replied, “It’s especially hard being around my son at night. That’s when I have really bad anxiety. My son wants to cuddle with me and I can’t. Because I’m afraid. You know, if I wake up from a nightmare and my son is crawling on me, I might do something.”

Frame and his wife, Chris, enjoy a morning with their youngest grandchild, Tommy, who was named after his grandfather. Frame says it’s the morning time when his thoughts typically drift to comrades who died in Vietnam.

ChaCha Cardenas had to write a letter to Abe informing him that she had given birth to their first child, Martha., while he was in Vietnam. She was worried he wouldn’t make it home to meet his daughter.

Chris Frame says it took fifteen years of marriage for her to understand the struggle Tom was having with PTSD. Her realization came one day after he came home from work crying because he’d had a flashback.

Tom Frame says it wasn’t until the mid-eighties that he began healing from his PTSD. That was the time he started Chapter 210 of the Vietnam Veterans of America. He says being surrounded by other veterans was the first time he felt comfortable since returning home from Vietnam.